Here I discuss my views on the relationship between God's omnipotence and free will. The main question explored is "where does sin come from?" Since God is all-powerful, how can there be sin? And if it's from man or his free will, where does that come from?

The common explanation is that God has permissive will: He allows things He disagrees with to occur.

I partially agree with this. I do believe God's omnipotence ordains all actions on Earth, but I also think that God doesn't do this randomly. He creates everything including our choices based on actions He knows we'd take if we had the unlimited power and freedom He does: counterfactuals. This preserves God's omnipotence, while removing the objection that God randomly assigns some to Hell.

So I basically argue for Molinism but with a twist: no permissive will and our free will exists only as counterfactuals and not in this universe: determinism in physical reality. God creates us based on what our choices would have been if we had free will.

Permissive Will

Permissive will is where God creates beings and allows them to do anything including sins. Bell's Theorem and possibly the Free Will Theorem could suggest non-determinism and genuinely stochastic models of quantum theory such as rGRWf. [Goldstein et al. "What Does the Free Will Theorem Actually Prove?" Notices of the AMS 57.11 (Dec. 2010), p.1453] While stochastic models of Quantum Mechanics (e.g. rGRWf) allow for truly random particle paths anyway, they are within a probability range. Even then, the randomness is due to the probabilistic laws themselves, which don't prevent it. And there are deterministic models (Bohmian mechanics, Superdeterminism, Multiple Worlds Interpretation) that negate this randomness. Besides, the universe wouldn't be (provably) random with respect to what made it. So one can't use this as an example similar to God's permissive will.

The problem I have with permissive will is if something cannot come from nothing, in what sense is God "permitting" anything without actively constructing it? How can He allow someone to sin if there is no power other than His?

The idea that He can create a being and give it power does not answer this in my opinion, because how can God give the power to someone to be able to sin? Even if we accurately observe that sin is not a "thing", it's still real from actions. How can an omnipotent being create something that goes against its will? It's like trying to make a force that does random things: how can an omniscient, omnipotent being create randomness with respect to itself?

Defining Free Will

What does "will" as a force consist of, the way electricity has electrons? This probably can't be answered the same way. If free will had a particle which was its essence, then it would negate its independence from the physical world and imply free will doesn't exist. One can argue the electricity in our brain when thinking results from free will, rather than being the free will; how speech results from thinking and isn't thought itself. Besides, one could ask the same question about the forces of nature, matter, or even space itself (Zeno's Paradox of Place): at what point is it something else? If you keep breaking down matter to atoms, subatomic particles like quarks, strings...at some point it's something else and then nothing else "just like that".

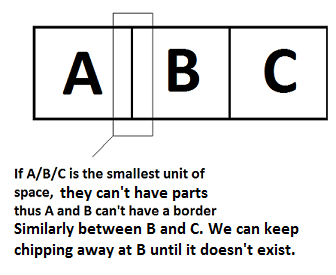

This non-constructive proof can't be avoided by saying space-time might be discreet as in loop quantum gravity. This is because if we take the three smallest units of space - A, B, and C - and put them next to each other, where is the border between A and B? Since these are the smallest units of space, there can be no border between A and B. Same for B and C. Thus B doesn't exist (at least without convergence - Paradox of Concentric Circles)!

Nor is this avoidable if we suggest a "jello-like" substance that doesn't have a smallest unit because we're right back to the same situation as continuous space-time: you can always zoom in on more "jello".

Free will's origin doesn't have to be from the universe, like the origin of matter itself. It also doesn't have to be located within space-time but can be independent (see Zeno's Paradox of Place). Like force carriers, its power doesn't have to be from the universe but can be its own: quantum fields are fundamental features of the universe itself. They don’t come from the universe in the sense of being emitted by it; they are part of what the universe is.

That such a force can exist is sufficiently shown by the no-contact forces of nature. Under any interpretation of Quantum Mechanics (including superdeterminism) you have changes in inertia without physical contact.

Another objection can be cleared up easily. If someone denies that free will is special by saying: "If a person has consciousness, then does a cat? An ant? An atom? And on the other hand, if a cat doesn't have free will, when does a person get it?" But this is just the Sorites Paradox: vague definitions. And free will is a metaphysical component. Moreover, it's entirely possible that, like Plato's Cave, we represent our actions if we had free will, but are entirely natural: kind of like how a tape recorder plays someone's actual words but isn't the person itself. Some of this also explains at what point a baby has/uses its free will, as well as mental disabilities: a thinker behind the thought isn't nonexistent anymore than a faulty telephone makes the speaker defective or fictional.

Free Will Mechanics

Nature of Intent

How can this choice be anything without some representation in reality? In other words, how can you have free will without being able to choose something in the universe, hence is your free will somehow co-dependent?

Intent may seem to require something in which it's contained, as well as objects it can intend. How do I intend "good" or "bad" without a universe? But, if the universe can simply exist, then it is entirely possible for any other entity to do so as well. Otherwise, we have Zeno's Paradox: what's the universe contained in? And what's that contained in? And an infinite regress simply exists all the same. And this would be the "location" of free will and origin of its power and choices.

Origin of Choice: Good and Evil without Temptation

Where are the movitations for any choice in this scenario? How does the decision "I choose to do good" vs "I choose to do evil" arise if there are no motivations (=influences/temptations)? How can I feed a man if hunger doesn't exist and I need to create it?

If I accept that random outside forces are not responsible for my personal choices, then why do I make any choice? A metaphysical origin would just move the problem to external forces outside the universe. If I say "out of nothing," then it's either a random impersonal force - which implies determinism - or there must be some mediator which only brings the question up again.

But one does not need motivation to do good or bad. I don't mean psychopaths, although I guess it could be boiled down to that. Basically, if any being had unlimited power and knowledge, it'd be either a malevolent or good. There wouldn't be any motivation but a person's own pure, uninfluenced decision to be just or not (John 3:19-21; 1 Cor. 10:13). This being would make a reality suited to his tastes. What these tastes are, or more accurately would be, is how God judges, and is probably how Satan and the demons got kicked out of Heaven.

It's a misjudgment to presume that temptations always cloud the issue of "pure" choice, since they actually reveal it. It can reflect a motivational vacuum where a being does either good or bad.

Counterfactuals

Counterfactuals are central to God's knowledge and our free choices. They are what one would do under different circumstances. If my choices are free, then there should be no machine or method to determine them with 100% certainty under those other circumstances. But this is true only with respect to the causality within the universe because it implicitly presumes naturalism and determinism: the information is only from this world, as noted above.

But are counterfactuals real? After all, by definition they are alternate actions that will never take place. So they don't exist, but could they have? Are they valid?

It's easy enough to demonstrate they are. If there is no God, then the universe is random how it is. That means there were other possibilities. If an omnipotent being exists, then it could've made it another way. So either way, we have valid alternatives.

Vagueness

There's a problem with counterfactuals called vagueness. This means that one cannot know what truth value they actually have. For example, if I didn't drink wine yesterday, a counterfactual world where I did could have the following equally valid counterfactual conclusions:

- Yesterday I drank wine and it was good

- Yesterday I drank wine and it was bad

Since this is an alternate world where both of these are logically possible, one cannot really define the counterfactual "I could have drunk wine yesterday" in any determinable way. But this is an issue for attempts to formalize their logic semantically and it does not relate to counterfactual validity itself. It is possible that counterfactuals' truth values are indeterminate and many logicians consider this to possibly be the case. But no one is arguing that they are invalid because of our inability to define them, and the main reason we can't define them is because we necessarily look at it from the point of view of our actual reality. Like the Monty Hall Problem, the same scenario (two doors) can have contradictory results due to mutually exclusive initial setups, just like with the counterfactual example above (strengthening the Antecedent).

Scriptural Support

Where are counterfactuals in Scripture? Matt. 11:20-24 is probably figurative, but there is an interesting connection between valid "what ifs" and God's judgment in Matt. 5:27-8. When Jesus says lust in one's heart is sin, it is all purely mental. While it's true that the intent does exist, there is no result; only a valid counterfactual that would be true if that person could enact his inner thoughts.

Modal Collapse

One can legitimately ask, "which version of an individual's counterfactuals is judged?" I might be a waiter or a painter if I was born in Canada instead of New York. So how can God judge one over the other? But this misunderstands the counterfactual. The scenario is where one has uninhibited free will and the power to execute. Impossible to be sure, but that's not what validity is. It's impossible for God or the universe not to exist, but it's logically valid if one or both hadn't. Therefore, an individual would have only one set of choices, or they'd be random and guided by some external nature or reality, not from his will.

This implies there are an infinite number of such beings. Since the number of humans will be finite, there are an infinite number of angels and demons (though either the number of angels or demons could be finite, but not both). Although a being with unlimited power has an uncountably infinitely many possibilities for an action, its choices become countable and thus one being - just as pi or any irrational is part of an uncountable set but is one, precise number.

Nietzsche's Question

A being's choices are not random with respect to itself, but they are with respect to the universe: it will choose something based on what it wishes, but the universe cannot predict this choice. Like the sqrt(2) being logically predictable in its digits (unlike a transcendental irrational like pi), but these are still random with respect to each other. The choice can be random in its output (what you choose), just not in its input (it's always you and not some outside force who chooses for your reasons). Since this intent is uninfluenced, it would be the same. Therefore if the universe "resets", the same choices would be made, if the same exact conditions were recreated. Similarly, you choose the same type of friends for the same reason - not randomly.

A man wanting to say "apple" in one language would use one set of sounds vs those for a different language. But the "source" would always be his intent to say "apple". Similarly, a person's choices would be the same if the universe were to "reset" and recreate the circumstances in every detail - or else his choice would be inconsistent with...his own choice. This "source" means that depending on the "model" of reality (i.e. if the universe were different), he would have different predictable choices (counterfactuals as well as reality).

Free Will vs Omniscience

A classic problem: how can we have free will if God is omniscient. If He can know our choices long before they're made, are predetermined and immutable?

Either the future is set in stone like the past, or there are multiple possibilities: future contingents. If choices can make history go one of several ways, then physical reality cannot influence free will the way gravity makes a waterfall go down. In this case, the independent choice is free from space and time and so God can know it "beforehand".

In a way, this is shown by the fixed past. If you watch a movie you've seen before you know what the actors will do or say more or less exactly, but those actors still had a choice in making those, predictable for you, decisions. But this goes further and posits that God can legitimately know what you would do if you lived in a different city/country, or had different characteristics. So this goes against Open Theism, which says that God is limited in his knowledge in situations like these.

If I know someone, I can generally know their reaction to something. This was realized by Gödel who says,

If I know someone, I can generally know their reaction to something. This was realized by Gödel who says,

There is no contradiction between free will and knowing in advance precisely what one will do. If one knows oneself completely then this is the situation. One does not deliberately do the opposite of what one wants. [DePauli-Schimanovich, W. and E. Köhler (2013). The Foundational Debate. p.116]

Logically speaking, it's impossible to do the opposite of what you want to do.

However, since these choices are neither random, nor "foreign" from you (in other words, they're your choices entirely and are also not predetermined), ontologically speaking these choices are you: they're your mind at work. We're not different from our free will, we are our free will. If we ask "where" the mind exists or "what" it's composed of, it can be a fundamental force just like any other. But this "essence" of your choices being you means that no one else can predict them, exactly because no one else is you. You can because there's no prediction involved: you're simply acting. So how can God or anybody else know your choices if no one else is "you"?

But imagine you went in a virtual reality machine for an hour. Then your memory is erased for that hour and you go in again. We established you'd make the same choices the second time, or they'd be random and not from you. Any observer would then know your choices. If we object that differences on the atomic scale make a 100% recreation impossible, then imagine a reset: is it impossible for God to rearrange all particles to where they were an hour ago?

Knowing the true intent of a person's will enables knowing his choices in any circumstance - the future or alternate scenarios. Like someone telling you a plan. Hence God doesn't need to see us live an eternity to know these choices. Thus also elect angels have never suffered, while demons fell like lightning (Luke 10:18) with no redemption (2 Pet. 2:4)). This isn't determinism any more than me knowing my own choice is.

Free will is independent of space-time, therefore it can be applied to any temporal reality (counterfactuals) and known. If someone's free will is a constant, then God is simply presenting one form of our fundamentally unaltered choices in this particular universe. Like code written for Linux is different for Mac, but has the same intent and output. Since we're all different, the same intent can be reflected by different output. For example, the same word in different languages. But a "rose" by any other name is still a rose: the intent behind is the same, even though the physical result is different. And if I couldn't speak, I'd think it. Similarly, God can know what one would do even if He didn't create them. Because another's existence is something God creates, He doesn't need the legalism of technical existence to tell Him anything: just as I don't need to finish a race I intend on running to know I will run it all the way (barring obstacles: not a relevant objection as we examine unrestricted intent).

Created but Uncreated?

- How can God know this "fundamental" free will before or without it ever existing, if it's autonomous?

- Doesn't that also make it not created by Him?

(1) A popular definition for knowledge is "justified true belief". This obviously implies learning if one is justifying it. However, contactless forces in nature show that information doesn't need physical transfer. Gluons, the force carrier particles, do not directly, physically interact with atoms, etc (fermions).

In Quantum Mechanics, being "in two places at once" really means the particle's state is a coherent superposition of spatially distinct possibilities. This is not a metaphor: it's exactly what the math says. The neutron's wavefunction simultaneously has amplitude in both paths until a measurement (or decoherence) forces an outcome. Superposition is mathematically real and has physical effects (interference, entanglement). It has real physical consequences. Even massive molecules (like the ones in double-slit experiments) behave as if they are in superposition, because the interference pattern depends on the wavefunction having multiple "paths". So, something corresponding to the superposition is experimentally real, even if it isn't a classical object in multiple places. Entanglement and multiple systems allow this "hidden information" (non-local - Bell's Theorem) to produce observable effects like interference fringes, quantum teleportation, and Bell inequality violations. [Lemmel et al (2022). "Quantifying the presence of a neutron in the paths of an interferometer" Physical Review Research 4, 023075]

The universe and time had a beginning. At t=0 either there was information (laws of physics, matter) or not. If there was, then information exists in 0 time: hence knowledge without learning. If not, information appeared out of nowhere at some point, which leads to the same effect: information without causality or origin. This is how God can know things without verification - even things that do not exist in synthetic reality (i.e. the universe) like counterfactuals.

This answer applies regardless of what Quantum Mechanics interpretation one takes: whether Copenhagen, Bohmian, or even Superdeterminism or MWI, because the collapse is still contactless, in this universe.

(2) And since counterfactuals don't technically exist, they don't contradict God's omnipotence. The objection that this is a "truth" that God didn't create is unfounded because since counterfactuals are logically coherent but don't exist, they are valid, not true. It's like saying "If God didn't exist and there was no universe, there'd be nothing" is a truth God didn't create and contradicts His omnipotence. It's validity; kind of like how statistics isn't anything but still applies to a coin toss. Nominalism doesn't refute this because it applies to truth and not validity: I can theoretically have an Earth with two Moons, but until I do there's no other Moon - and so perhaps confirms that counterfactuals don't contradict God's omnipotence.

God's omniscience or will is also not in question, because God cannot know His decisions before He decided them, thus there's nothing to know and doesn't contradict omniscience. To suggest otherwise is a Halting Problem. Counterfactuals do not precede God's knowledge chronologically (the definition of learning), only logically (the definition of knowledge), as William Lane Craig puts it. This is like the tautologies above, or how 2+2=4 is timeless, yet you need to add the 2's before you get a 4.

Determinism

Some misconceptions are common. "I can't teleport" is really a physical limitation. I don't choose to be hungry is a first-order desire and not a voluntary action. Influence is external and also not evidence of determinism but merely limitations of free will that reflect the limited evil we are capable of.

External causes impacting the expression of choice is not the same as creating that choice. Imagine a computer virus that changes W's to R's, so instead of "who," the computer shows "rho". The computer didn't move your finger to press "R" for "W". A response to something in nature does not mean nature took over your free will. Proof of this is habits: I don't consciously think about how I ride a bike when I ride it, but I chose the activity. Breathing is also semi-voluntary. It's like a ball's trajectory after I throw it: deterministic, but my choice where I throw it.

Moreover, the mentally handicapped or children are not any less with free will. If a telephone cuts in and out, I don't attribute the disrupted dialogue to the speaker on the other end.

Axiom of Choice

Hardin and Taylor argue that the future can be perfectly predictable based on the Axiom of Choice. [Hardin, C.S., & Taylor, A. "A Peculiar Connection Between the Axiom of Choice and Predicting the Future". The American Mathematical Monthly (Feb. 2008), 115.2: 91 - 96] Set Theory can be used to extrapolate the future based on past events with 100% certainty. Their μ-strategy uses the fact that the past is unchangeable, events can have an infinitely countable number of variations, but there are an infinitely uncountable number of variables. In other words, every air molecule in a particular wind blew one way, but there were an uncountably infinite number of factors (direction of the wind), meaning that based on this past event, the future could be known which way it would blow because that's all it can do as shown by the past. Since the past has specific, albeit unknowable as the authors concede, values meaning they're an outcome with countable results, then the variables, which due to the genuinely random, stochastic nature of particles makes uncountable in their number, must actually be countable and thus predictable by a determinable function.

Even if they're correct in making every "instant" of the past countable [Hardin & Taylor, 92] when the future variables are uncountably infinite, this is not determinism. Their model is a statistical strategy that fails a finite number of times but succeeds an infinite amount. [Hardin & Taylor, 92] It's also based on a theoretical infinite past. It's like flipping a coin and getting tails 10 times in a row to bet the next flip will be heads: but on an infinite scale. It's similar to how an irrational like sqrt(2) has random digits but is perfectly predictable by the operation of taking the square root. This is also why the Monty Hall Problem isn't 50-50.

In addition, the whole strategy only works with a non-sentient randomness in the universe. Because an agent who can intentionally create a result can actually make the future unpredictable, akin to me flipping a coin in a way that it produces tails an 11th time. [Hardin, Christopher S.; Taylor, Alan D. "An introduction to infinite hat problems." Math. Intelligencer 30 (2008), no. 4, 20–25]

Pawlowski also objects: if we placed an "uncountably" infinite number of socks and a "countably" infinite number of skirts in a (bottomless) bucket, we should expect to draw a sock once in a while, whereas the μ-strategy says this could never happen. [Pawlowski, Pawel. "Philosophical Aspects of an Alleged Connection Between the Axiom of Choice and Predicting the Future" in Applications of Formal Philosophy (2017), p.216]

Experiments in Neurology

The conclusion from Benjamin Libet's 1980's experiment that seemed to suggest that choices were predetermined neurologically outside (before) the conscious decision/intent of a person has recently been reversed. In a recent experiment that measured the phenomenon of choice more accurately with better conditions, Schurger et al determined that Libet's experiment had the mistake of allowing individuals to know too much time before they were to make a choice. The actions simply weren't spontaneous enough, and once these became quicker and less predictable, the supposed unconscious decision-maker Libet found was shown to be simply neural "noise" that was independent of the actual decision-making mechanism. In other words, our random decisions are predicated upon a moment during which this neural noise "nudges" us to then actually pick it as the random moment, without being the actual choice itself: like a whim essentially. Since one random moment is as good as another, this makes a person have no reason not to "go with the flow". [Schurger, Aaron, Jacobo D. Sitt and Stanislas Dehaene. "An accumulator model for spontaneous neural activity prior to self-initiated movement" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Oct 2012, 109 (42) E2904-E2913]

Other ideas focus on the illusion of consciousness. Blackmore and Troscianko mention some interesting experiments in their Consciousness: An Introduction (3rd ed.). "Don't think of a white bear" is an impossible proposition because you need to do two contradictory actions: think and not think. But this is simply a tautology, not proof against the agency of free will. They also mention how audiences in magic tricks frequently make choices that were actually forced by the magician subliminally or through other tricks. In fact, the atheist magician who uses suggestion, Derren Brown, even alludes to the fact that "Don't think of a black cat," is simply logic.

Influence through wordplay is undeniable. But altered mental states say nothing about the existence of free will anymore than being sleepy or drunk does. Everyone has experienced conscious or unconscious influence in decision-making. But if I define free will as pure choice, then clearly mechanisms of the brain as opposed to the mind can take over - e.g. breathing or blinking which are defined as "semi-voluntary": I can do both consciously or unconsciously. I can move at will, or it could be some kind of reflex. One percent free will is still free will. The burden of proof against free will is to prove there is 0 percent. So neither NLP, nor mental tricks, nor the table-moving seances that Faraday's experiments showed were unconscious movements by the people despite their firm belief it wasn't prove anything against volition.

The same is true with an experiment in 1963 by William Grey Walter where subjects would change the slides in a projector, but unknown to them, the slides changed by increased activity in their motor cortex before they actually pushed the button. They reported surprise, and Blackmore and Troscianko conclude that consciousness is not a prerequisite for personal action and that voluntary actions are an illusion if unrecognized. This may be true, but the experiment doesn't show this: the subjects were expecting the slide change after the physical button press. They certainly knew they were in the process of pressing the button. It's like saying if I expect to turn the lights off in my mind before I actually touch the switch that it was never my intent to turn them off: that's simply the definition of surprise! Strangely, they say Libet's much more direct, objective, and time-sensitive experiment requires "artificial judgment...about the timing of will" (p.237).

Another experiment focused on influencing decisions. Daniel Wegner devised a game where two people sat opposite each other across a table. They had some images of objects in front of them. They were to hear random words for 30 seconds through headphones and pick an object at will during 10 seconds of music after. One person was a genuine subject, the other, unknown to him was receiving instructions to place their hand on specific objects. This object was mentioned in the genuine subject's headphones from 30 seconds before to 1 second after the other placed their hand on it. This happened 4 times, and the rest was genuinely random. The idea was to see if the words in the headphones and visual cues of the other person could influence someone entirely yet make them believe it was their choice. The strongest "choice" was 1 and 5 seconds before the other put their hand on the same object mentioned (1 or 5 seconds before), and weakest 30 seconds before and 1 second after. The 30 second delay clearly eliminated the intensity of the suggestion, and shows these are just whimsical influences like NLP: time-sensitive like being sleepy at first and then becoming more aware. The experiment only proves the existence of consciously following (or allowing?) unconscious whims.

What Wegner's game does prove is that, yes, consciousness can be divorced from decisions. But how is that different from an animal's choices, or AI? As mentioned above, influence exists, but does not by itself prove anything against volition, anymore than a person's actions in a dream which they are fully conscious and believe are theirs do.

Alternate Ideas

Predestination

Single predestination - that all good comes from God - was never denied by the early Church. But double predestination, that God creates men and ordains their condemnation, was a heated debate in the 9th century. The proponents argued that God's omnipotence does not allow for anything but double predestination.

This idea is pretty obvious. We don't actually have free will, but we're automatons with the illusion (both to ourselves and others) of having one. Descartes considered animals to be simply complex machines, and today in the robotic age, we can't completely throw away the idea that we're not that either.

Some even suggest that we're still punishable for "our" actions, because God is the definition of justice, and He does whatever He does. The reason some are accepted and others aren't is because of this same principle, but he rejects some "for his glory" and to contrast them with what's good: sort of like how yin and yang need each other to exist - or the fact that the stars are only visible in the night, when they're contrasted with darkness.

It's not a contradictory mechanism for the relationship between free will and omniscience (+omnipotence) for the simple reason that it essentially denies the former. However, I feel it's not the only solution.

Open Theism

Here God can't and doesn't know the future beyond what can be physically known (or guessed). Naturally, it's not a very popular view because it denies God's omniscience.

The proponents of open theism consider it a more biblically-aligned view. They object to traditional concepts of omniscience on the basis that it originated from Greek thinking. God in the Bible has a conditional policy: if you obey you're rewarded, if not His presence isn't with you. Judgments and pronouncements are frequently shortened or abrogated (the three day plague because of David's census reduced to one day). In Genesis he sends two angels to find out the true extent of Sodom's sins and what punishment they merit. Abraham is tested so God can see if he has true faith and would sacrifice his only son whom he got after so much hardship.

I disagree because God's judgment may seem relative or non-final only because it's pronounced with respect to human actions, which are of course conditional. Omniscience plays no role because God would react positively for obedience and the opposite for sin, so of course it's a conditional tautology. If man is here to convict himself, then it would be presented as one. Where God changes His mind is either not necessarily final (one can always know one would change His mind, much like reverse psychology), or it's from the point of view of man.

If one thinks God needs angels to report to Him, it's a little odd that He'd know every man's thoughts. If these are invisible (Num. 22:31), then obviously the visible angels sent to Sodom were meant as a symbol. Yet David's secret desire for Bathsheba and how he dealt with Uriah was known to God - no reporting by angels needed. Abraham's thoughts would've been known (Prov. 15:11). If everything is under God's control (Prov. 16:33) He doesn't exactly need tests or messengers to know things. The tests are clearly from man's point of view for his benefit (Hebrews 11; 1 Timothy 3:15-17).

Ultimately my objection is not that it's invalid, but because it creates a number of other differences. It's not only that we can't know if there's another god, perhaps more powerful, that could exist. But if God is not omniscient, then how could he be just? If he doesn't know everything, then he can't be perfectly fair in deciding how to deal with actions which he technically couldn't always know are errors anyway: he might not know their full extent, he wouldn't know if the situation testing a person was unfair, and his definition of error might be flawed. If God is omnipotent but doesn't utilize this omnipotence with omniscience, then He might actually become morally wrong by excessive or incorrect punishment or reward! This is not necessarily true, but it becomes a possibility.

Again, this is all valid, but the real problem lies with the fact that free will, which apparently has some kind of power over God's knowledge, now has to be more powerful than reality itself (to not be controlled by it and be independent). So the order of power becomes: free will, the universe, God (who can't see the future).

If we are to believe the Bible, God has a list of names in the Book of Life (Revelation 20:12). If we are to believe Open Theism, God is constantly revising that list and needs to investigate to complete it, and best of luck to you!

Compatibilism

Compatibilism is the idea that determinism and moral responsibility are compatible. At first this idea might seem counter-intuitive and impossible: if the way I was born determined my choices and who I am, how can there be any merit? It also seems to presuppose naturalism and anti-metaphysical reality. Because that's the only explanation for our behavior and existence, and our behavior is therefore judged impersonally as a force like gravity which is nevertheless present and real. For this reason incompatibilists reject that the two concepts are not contradictory.

But a closer look dissolves some of these extreme conclusions. For one, God's omniscience and man's responsibility is a central tenet to most of Western theology. Influence is undeniable, though its extent is presumed to be within the limits of the individual's abilities of conscience (1 Cor. 10:13). Moreover, if the supernatural exists, then the universe is merely an expression of an individual's choices that is inevitably determined from its own configuration. For example, I don't have wings therefore I will never choose to (naturally) fly, because I can't.

The key difference, however, is that there is a "true" choice, somewhere, outside of nature. Like a telephone, there is a speaker "behind" the machine. FOr this reason incompatibilists have devised three fundamental arguments against compatibilism:

- No one has power over the laws of nature, therefore just as the past is unchangeable, so is the future (Consequence Argument)

- Free will entails the ability to choose one option from many (Principle of Alternate Possibilities)

- A person is the ultimate source for his or her choice (Source Incompatibilist Argument)

The first argument can be challenged even in a naturalistic worldview. Alternate possibilities are real, especially since the nature of reality including its laws would be random. For example, in Quantum Mechanics, a particle can shoot in a truly random direction after radioactive decay - instrumental in Schröndinger's Cat thought experiment. This provides a basis for counter-factuals for compatibilists.

The second argument can also be easily shaken. Imagine Lee Harvey Oswald on the day of JFK's assassination (if you believe he was the only one who did it). Now imagine there's a demon that takes away Oswald's free will should he pull away from assassinating Kennedy. So if Oswald decides to go through with it, for his own reasons, he clearly has free will (some free will is free will: if I can choose one of two options instead of one of three). If he doesn't, he's not responsible, but he simply doesn't have the option of his finger not pressing the trigger.

Clearly he has a choice, despite the fact that it's his only option. The fact that he has his own reasons might suggest that there are multiple options within that option he's choosing from. But we can easily show that's not the case. Imagine that for every degree of option-choosing he makes, the alternative option is denied by the demon, who is willing to take control of him. Whatever positive, proactive action he takes or conversely inaction he prefers would be his own choice, with no other possibility. He still has a choice, but it was his only option. This is called a Frankfurter example, after Harry Frankfurter. It clearly shows that the rule that free will needs alternatives is misguided and illegitimately tries to turn nature into a responsible, moral agent itself! All this really proves is that the past is as unchangeable as it was a choice. This is also an important observation and realization for later: that some choice is still fully choice.

The Source Incompatibilist Argument, however, has met with much less success in my opinion from compatibilists. The various attempts at invalidating it simply highlight to my mind the inescapable problem with compatibilism. There are several schools of thought:

- Free will is merely following desire unopposed (Classical Compatibilism)

- Desire itself can be manipulated by factors that, using the above definition of free will, create the contradiction of choosing and not choosing something at the same time. If I can't fly to the store, I would always choose to walk, run, or drive to it. I both choose walking out of desire, and don't choose flying out of a (potentially stopped) desire regarding that inability.

- Morality's definition is intrinsic in human nature to some degree, hence unchangeable and thus unchoosable; we have programmed responses like waving hello to a friend (Reactive Attitudes)

- This begs the question by not only obviously assuming predeterminism, but ignoring that instinct is not choice.

- Counter-factuals can exist in determinism (New Dispositionalists - two schools)

- This merely shifts the problem from the expressive act to the "causal base". It's like trying to claim that a mathematical formula where "X" is in miles instead of kilometers means it's not a static, determined formula. Or the phenotype (expressed characteristics of someone's genetics like brown eyes) is fundamentally different from the genotype (the genes unexpressed, like the recessive alleles for blue eyes). Frankfurter examples do not contradict this though.

- First vs Second order desire (Hierarchical). This idea distinguishes between what you immediately want such as impulses or instinct vs what you truly want logically. For example, you could be on a diet and not want to eat sugar but crave it. Also if I was born predisposed to like ice cream (reactivist/natural compatibilism theories)

- Same problem as the above two; also the the problem can be seen that you partially want something. And if you're addicted to drugs or brainwashed you could believe you want something that mixes the first and second (and other) order desires, making it obvious these are arbitrary constructions. This is essentially also the main objection against Classical Compatibilism: if determinism and responsibility can coexist, how can you know when you are truly the responsible party? As far as ice cream goes, this is definitely a choice based on a preference that was determined (by nature or nurture). But your action upon it is when it becomes your choice: you don't choose to enjoy strawberry over vanilla, but you're the one who decides to buy a strawberry shake rather than a vanilla one. As such, the preference simply becomes an influence. The idea that influence makes a choice at least partially deterministic is not only debatable, but irrelevant exactly because of the Frankfurter examples which prove that 1% choice is still choice. Paul employs similar logic when he states that "if part of the dough is holy, then the whole batch is holy" (Romans 11:16 - e.g. if part of a container of water is clean, the whole container must be clean). Hence, if your ability to express your true desires are not overwhelmed or overshadowed, you cannot charge another person or force with irresistible pressure (1 Cor.10:13) or entrapment.

- Physical determinism does not imply psychological (Susan Wolf)

- Impossible as SEP itself notes

- All free will is rational; if irrational, it is delusion (Reasons-reactive)

- like the first few reasons: still determinism

- Our choices are guided by pre-existent frameworks for deciding as well as judging correct and incorrect behavior (e.g. I can't change my accent no matter how hard I try)

- That's like saying the Big Bang made me do it: it's relative to something else, not the universe, hence illegitimate as a solution

- Our choices are a mere manifestation in reality of a prior, "outside" cause. For example, a telephone transmits a person's voice merely mechanically and deterministically, yet there is a speaker behind the electronic voice. This world is merely something like a computer generated program the way the inventor of the first computer programming language, Konrad Zuse, speculated it could be (in his Rechnender Raum (1969) [trans.: Calculating Space]); also more popularly explored in The Matrix.

- while this is actually a solution to how God could know whether someone such as a mentally challenged person would be a sinner or not, this wouldn't work here because it merely shifts the problem back to another, "outside" deterministic force. Zuse's idea is probably contradicted by Bell's Theorem, which although noted by James Bell to not work in a deterministic universe, certainly applies to ours which quantum mechanics probably shows isn't deterministic anyway (perhaps a blow to Compatibilism, although not necessarily, see below).

In combination with #8 above, we have the following situation: true randomness can be obtained by purely logical, rational, deterministic means. For example, pi has a truly random sequence of digits (3.141592...) that have no pattern, but it's merely a circle's finite circumference divided by its finite diameter. If one objects that one of them or both must be irrational and random, then we clearly have something like this in nature whose origin is deterministic (unless we presume God Himself is random). Moreover, all irrational square roots are numbers that have a non-random, rational square. Even the sqrt(2) to the power of sqrt(2) is rational! And since this is the logic of math, it must apply to and within reality.

From this observation, we can posit that an action can be begun by such a random trigger. For example, the famous Schrödinger cat is unpredictably dead or alive when one opens the box because the radioactive decay shoots a subatomic particle in a truly random direction, unpredicted and undetermined by anything before it. So imagine if every person's ultimate, defining thoughts and actions had that same origin, perhaps with some guidelines like predisposed behaviors, situations that taught him something, etc. This would be exactly the kind of picture the compatibilists want to paint - purely on rational, uncontradictory, and scientific grounds!

In this case one would have "true" resonsibility in the sense that his actions will be his own, yet they follow laws of the universe. In a way, it makes sense: if a bridge isn't strong enough, it'll collapse: it's not its fault, but it will be the thing collapsing. These laws are ultimately deterministic: just as the square root of 2 is always going to be the same, but its sequence of digits random. It's relevant that these digits are random because if this number can't be expressed as a fraction, then it clearly doesn't have any divisible parts (the way 1 can be split into 4 quarters), which means it doesn't really exist (it's uncountable, in Set Theory terms). Another way to illustrate this is the fact that 0.999...=1 exactly, not an approximation. This can be proven very easily by: 1/3=0.333...; multiply each side by 3, you get 3/3=0.999...; 1=0.999... This expresses the fact that a dot has 0 dimensions and the dot next to it (the "smallest" number lower than 1) is both the same dot and a different one, in a way - similar to exactly what we have in this compatibilist source of "free will" and responsibility.

- Since this is valid, and is the same exact idea developed above about how a person's choices are from somewhere AND nowhere at the same time (because of a misconception of one's point of view, causality, and time (illustrated by the, what one may call pseudo-math, just now)), this is the exact same thing except it posits that one's choices came from nowhere within the universe by laws (like Quantum Mechanics), rather than God creating man/his free will. There is no difference, except that Quantum Mechanics does not explain randomness anymore than taking the square root of 2 explains the irrational root's random digits (i.e. predicts them): what is undeterministic, is undeterministic, and the origin of anything random in the universe, be it a subatomic particle's direction or a square root, does not help compatibilism which requires determinism as far as I see it. Otherwise, there's no difference between Compatibilism's determinism and Incompatibilism's (metaphysical and perhaps equally unexplained/unexplainable) free will!! It simply shifts back #8 by replacing determinism with indeterminism and mascarading as "explained" (by vague, blanket terms like Quantum laws) random origin. This type of bias and legalistic fallacy of words is exactly the problem one runs into with the Sorites paradox (aka Theseus' Ship). Simply put, if by definition it's random, it's undeterministic, and as I see it, Compatibilism needs full determinism. And as it's intuitive, this simply is a contradiction with responsibility.

Calvinism

Calvinism shifts the focus from the mechanism of God's knowledge, to its implication. It's irrelevant how you got to your actions versus what they are. In that sense, man doesn't have "libertarian free will," but his choices are dictated by God's will (which is the only truly free will). It's not so much that you don't have choice or responsibility, but your corridor is narrowed. A blackjack computer program will never deal Texas Holdem.

If we see God in a sort of semi-passive role where humans are born into "weakness of will," then responsibility seems to falter for man. This isn't the typical idea that "you have a choice, but you're very inclined to make a different one" (i.e. influence - temptation). Here, without God's direct intervention, man is 100% doomed.

The twist is that since God is omnipotent and omniscient, He makes man responsible. This essentially boils down to "right by might," but it is not invalid. Throughout this entire article we've been assuming that responsibility and fairness are defined by equilibrium (i.e. I cannot be responsible if I never had a choice). But we all know that reality doesn't play like that. A genius like Mozart never worked to be the great musician he is. It was simply a gift he was born with: talent. Does that make his music any less good?

But here guilt for the unsaved is inescapable. John L. Mothershead rightfully observes that in such a scenario there can be no responsibility (much like Compatibilism). Since humans are born in weakness of will, it's God who picks and chooses to save some, without whom they'd be lost like the others. And Romans 11:28-32 is clear this isn't the case (the subjects are both the saved (v.30) and unsaved (v.31)). Since the basic presupposition is that man is responsible because he could've done otherwise, this arbitrary idea is just as valid as the idea that a giant rock in the Sahara is responsible for all decisions in the universe. There's just no common ground and anyone is free to believe anything at such a point of divergence.

Conclusion

Boiling it down:

- Choice is not a product of temporal reality, therefore it can be known at any point in time within temporal reality

- Choice is an action from free will, independent of space-time, therefore it can be known within any temporal reality (counterfactuals): it occurs simultaneously with respect to a person operating it, because it is a person operating it. As such it's independent of space-time, but like inertia (which Feynman notes has no known origin), exists within it./li>

VI. References

- Hardin, C. S., and Alan D. Taylor. “A Peculiar Connection between the Axiom of Choice and Predicting the Future.” The American Mathematical Monthly 115.2 (2008): 91–96. JSTOR

- Mothershead, John L. Ethics (1967)

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Free Will

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Compatibilism