|

|

|

|

|

Was Jesus and Christianity copied from ancient pagan myths?

Showing that Christianity did not syncretize anything in its religious beliefs from other religions

|

|

|

|

|

There are some who claim that Jesus was invented by the early followers of Christianity based on pagan myths and deities. They also maintain that beliefs and doctrines in Christianity also have that origin. These skeptics argue that Jesus resembles the numerous pagan deities throughout the Near East, Greece, Rome, India and elsewhere.

We will see in this article that this is very far from true! I'd first like to add that the similarities between Jesus and other pagan gods are often so strained that it takes more faith to believe the myther's logic than Jesus' existence. In other cases, the similarities are so broad (such as both being "the son of God") that this is an obvious case of parallelomania.

In any case, here's a list of the alleged similarities between Christianity and other religions with explanations why Christianity did not borrow or syncretize with them in the way skeptics of the Bible claim.

I. Introduction: Parallelomania and similarly fallacious logic

Throughout history many cultures have shared and borrowed ideas from each other, a process called cultural diffusion. This of course extends to the borrowing of religious ideas and gods as well. For example, the Syrian moon god Hubal eventually made its way to Mecca, where it was the most popular god whose idol was found in the Ka'ba.

But just as easily as religious ideas may have influenced different cultures, so can the imaginations of people, even scholars, be inclined to find links between religions where none exist. I will give a pretty famous example of the alleged borrowing of the Book of Proverbs from the Instructions of Amenemope. The parallels there in my opinion only show similarity in terminology and expression due to a common culture and time, supporting the idea that the book comes from the 10th century BC (the Instructions of Amenemope comes from around 1100 BC). This is one scholar's opinion on the matter:

The connection so casually assumed is often very superficial, rarely more than similarity of subject matter, often quite differently treated and does not survive detailed examination. I believe it can merit no more definite verdict than 'not proven' and that it certainly does not exist to the extent that is often assumed...The parallels that I have drawn between [the ueuetlatolli of the Aztecs], (recorded by Bernardino de Sahagun in the 1500s) and ancient Near Eastern wisdom are in no way exhaustive, but the fact that they can be produced so easily underlines what should be obvious anyway, that such precepts and images are universally acceptable and hence that similar passages may occur in Proverbs and Amenemope simply by coincidence.

The point isn't about whether there are or aren't any direct literary connections between Proverbs and the Instructions of Amenemope, but that one can find similar parallels between the ueuetlatolli of the Aztecs and the Near East, where there is no influence in either direction, but merely an expression of wisdom coming from natural observation. In the same way, many parallels between non-Christian religions and Christianity are nothing but coincidental similarities that are stretched, at least as far as this article is concerned, usually by people who desperately want a connection to exist.

I will give another example. A long time ago, someone wrote a story where the ghost of a prince's dead father appears to him to warn him that a conspiracy by those closest to the king had killed the young man's father, and so that he shouldn't trust anyone. Sound familiar? Shakespeare's Hamlet you say? Nope, this is the Instructions of Amenemhat from around the year 1900 BC! Yet compare the similarities between this ancient Egyptian piece of wisdom literature and Hamlet Act 1, Scene 1. But certainly Shakespeare wasn't influenced by the Egyptian writing (nor, of course, the other way around), since the Instructions of Amenemhat was found around the 19th century.

This whole situation is very human in its inclination to connect things where no connection exists. This has become even more redundant because the authors regarding this subject have always been extremely eager to find dependence by Christianity on other religions. An example of this inherent trait to connect unconnected things is when J.R.R. Tolkien heavily criticized a Swedish commentator who suggested that The Lord of the Rings was an anti-communist piece of literature, Sauron, the main evil character being Stalin. Tolkien's anti-Communist stance was well known by then, but he answered, saying, "I utterly repudiate any such reading, which angers me. The situation was conceived long before the Russian revolution. Such allegory is entirely foreign to my thought."

Finally, there are three types of dependency that could have led to an influence upon Christianity:

A. Direct Influence - Here there is an active and consciouss copying of symbols, images, etc.

B. Indirect Influence - This is an unconsciouss copying, simply appealing to a common/popular idea or motif that existed at the time.

C. Common Human Imagination - This type of parallel means that the resemblance between two ideas (religious or otherwise) sprang up due to a common element in human thinking. This doesn't always have to prove imaginative forgery. Sometimes the common element is obviously an imagination (such as the heroic quests of various pagan religions' heroes such as Hercules and Odin), and sometimes it is simply because of something universal in nature (such as water used as a metaphor/symbol of cleansing and purification due to its cleaning properties). Since such results can be misleading, especially with the title of this category, only parallels/similarities that share more specific details will be included. I'll give two examples. One is the Flood story found in cultures across the world. For example, in the Finnish Flood story, the flood results from a wound in a (primordial?) hero's knee, which gushes out blood. This is somewhat similar to the Australian Tiddalik, though certainly there's no dependence, direct or indirect, either way. Another example is the similarity between the function of the Oval Office in the White House and the Grand Secretariat of the Ming and especially Qing dynasties of China. The Grand Secretariat, like the Oval Office, functioned to expunge unimportant information to the emperor so as to not swamp him with unnecessary work, though resulting in his inability to see what information wasn't shown - a problem that became a big deal in Reagan's presidency. Yet a final example would be the ritual of the "scapegoat" practiced shortly before the seasonal renewal in summer, such as the Thargelia of Athens and the related Greek cities, similar to rituals found in Tibet and Rome. So this is an example of a common human development, but something vague like "an ascension to heaven" won't do in this category, which is reserved exclusively for natural development in religion both ways, not just for one to resemble a true case of an ascension.

In addition to these, I propose three more categories:

D. Direct Influence by Christianity

E. Indirect Influence by Christianity

F. No Influence

These three are pretty self-explanatory. Of course, if there isn't strong evidence for any of the first five, then that's the only time the parallel would go into the "No Influence" category, but believe, that one

The evaluation of each aspect of Christianity (i.e. belief in Jesus' crucifixion, baptism, etc) and how strongly, if at all, it places in any of the above three categories is examined below in the Conclusion section of this article.

So with this in mind, we proceed to discuss below examples offered by some who consider Christianity to have borrowed some of its beliefs from pagan, pre-Christian religions, noting that virtually all of the examples here are examples of parallelomania.

II. Concepts and ideas in foreign religions that are not applicable

The purpose of this section is to explain why certain similarities between Christianity and other religions are not to be considered legitimate parallels. The rationale is that broad categories will often intertwine amongst religions, sometimes on a seemingly detailed level, yet have nothing to do with each other in terms of syncretism. So, for example, Romulus' ascension back to heaven is obviously the only thing Romulus can do after he came to Earth to speak with Proculus. Such a similarity is nothing but an inevitable coincidence. It's the same as two different people, each of whom mention buying a house in their autobiographies: it's bound to happen!

Of course, legitimate parallels between such broad categories are indeed possible. But these parallels have to include specific details that match up. So, for example, when Romulus' ascension is described as "lightning fast" (the same with that of Apollonius of Tyana), Jesus' slow ascent up until he is hidden by a cloud can be safely regarded as mostly uninfluenced by Greco-Roman miracle imagery. I say mostly because there are other aspects to be considered, such as the setting in which the ascension takes place (also completely different), and so on, though in this particular example I don't think there are any significant similarities between Greco-Roman myths of ascensions and that of Jesus Christ.

And so we take a look at each of these categories and why they shouldn't be considered legitimate parallels when such similarities do occur between non-Christian religions and Christianity.

Ascension to Heaven

Just about every religion and mythology has a god who is either born or descends to Earth, only to ascend to heaven later. The Greeks had Mt. Olympus, the Egyptians had Duat/Aaru, the Sumerians had Dilmun and so on. Obviously at some point in the mythology of each of these religions one or more gods are going to come to Earth for various reasons (or be born on it), only to ascend to the abode of the gods once again where they lived. That Jesus Christ should incarnate on Earth (vast difference from any other mythology) and later ascend back to Heaven is no parallel that necessitates for Christians to have overtaken from paganism in and of itself.

III. Non-Christian gods and heroes

Zulis/Thulis

This Egyptian god is completely unknown to mythology. The name comes from Kersey Graves' book, The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors. What seems to have happened is that Kersey Graves confused this Zulis/Zhule/Thulis/Thule with Osiris. Evidence for this is that he quotes an author named "Wilkison" (John Gardner Wilkinson, 1797-1875), who writes about this "Thulis". The relevant quotes Graves cites are to be found in Wilkinson's A Second Series of the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians Volume 1, pp.189-190, 320 (it can be found here). How Graves got Thulis/Zulis (and Thule/Zhule) from Osiris is a mystery.

VI. Christian rituals, concepts, and beliefs

"Christos" as a title

It is true that in pre-Christian times pagan gods and goddesses were referred to as Chrestos. But this has absolutely nothing to do with the title Christos. The title Chrestos simply means "good" in Greek, and is one of many monikers these gods had. The Greeks, Romans, and Greco-Roman Egyptians referred to their gods by various epithets and names. So for example, Apollo could be Apollos Musegetes (Apollo the muse leader), or Apollos Helios (Apollo the Sun). The same can be found for practically every other Greco-Roman god of importance. The difference in spelling between Chrestos and Christos might be very little (the difference in pronunciation in Koine Greek is practically nonexistent), but the meanings are vastly different.

The epithet chrestos was very popular throughout antiquity and the fact that even Socrates was called, "ho Socrates ho chrestos" by Plato, who uses this title of others, shows that this title was not the same thing as Christ. Acharya herself notes this and the fact that this was used by many other playwrights, as well as even by the Jews regarding God!

So for example, when there are pre-Christian inscriptions that mention Mithras Chrestos, or Osiris Chrestos, this has no relevance to Christos, which is Greek for "Anointed", the equivalent of the Hebrew "Maschiah". Thus it is a big misconception when someone like Acharya S writes that,

Moreover, like his earlier incarnation Osiris, Serapisóboth popular gods in the Roman Empireówas called not only Christos but also "Chrestos," centuries before the common era. Indeed, Osiris was styled "Chrestos," centuries before his Jewish copycat Jesus was ever conceived....

I e-mailed her asking for any pre-Christian usages of Christos and not Chrestos and none were given; her only answer to me was that she knew what Chrestos meant, after I explained that the two words in Greek are not synonymous. Well, either she doesn't, she's incorrect about pre-Christian (or at any time) usage of Christos for Osiris/Serapis etc, or she has some secret pre-Christian text/inscription that uses the Christos of a pagan god.

The whole error of Acharya S regarding this comes from Hadrian's letter. She writes:

Taylor also comments that, at the time this letter [by Pliny] was purportedly written, "Christians" were considered to be followers of the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis and that "the name of Christ [was] common to the whole rabblement of gods, kings, and priests." Writing around 134 CE, Hadrian purportedly stated:

"The worshippers of Serapis are Christians, and those are devoted to the God Serapis, who call themselves the bishops of Christ. There is no ruler of a Jewish synagogue, no Samaritan, no Presbyter of the Christians, who is not either an astrologer, a soothsayer, or a minister to obscene pleasures. The very Patriarch himself, should he come into Egypt, would be required by some to worship Serapis, and by others to worship Christ. They have, however, but one God, and it is one and the self-same whom Christians, Jews and Gentiles alike adore, i.e., money."

It is thus possible that the "Christos" or "Anointed" god Pliny's "Christiani" were following was Serapis himself, the syncretic deity created by the priesthood in the third century BCE. In any case, this god "Christos" was not a man who had been crucified in Judea.

At this point we should mention that Christians, Romans, AND Greeks were all confused as to the proper name for Christians. Some designated them as Chrestiani/Chrestianoi with Chrestus/Chrestos as the founder, others as the correct Christiani/Christianoi and Christus/Christos. Sometimes the incorrect name of Chrestianoi was purposefully given to make the point that Christians (Christianoi) were good men (chrestianoi).

This confusion is obvious in Hadrian's letter, who refers to the worshippers of Serapis as Christiani instead of Chrestiani (Serapis Chrestos). The name "Chrestos" in Egypt was apparently popular at the time as a shortened form for Serapis, and perhaps other gods, as the Chrestos bowl found in Egypt attests. And by Hadrian's day (the letter being written in 134), Christians were well known as a religious group - Quadratus had written a defense for the Christians to Hadrian himself in 125, so his familiarity with Christians is a very possible source for his confusion of them with the "Chrestians", the followers of Serapis he so designated.

And so, pre-Christian usage of "Chrestos" for pagan gods is irrelevant. And despite those who claim that there was pre-Christian usage of the title "Christos/Christus" for other gods and goddesses, there is none. Actually, however, there is one example of a pre-Christian usage of Christos as a religious title/description that I have found. It is found in Daniel 9:26, and refers to the Anointed One, the Messiah!

Crucifixes and the Cross

Despite the books of those such as Kersey Graves (The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors 1875), Gerald Massey, Acharya S, John G. Jackson, Tom Harpur and so on, there are no pre-Christian examples of crucifixion in religion. Knowing this, modern writers who contend that Christianity is still based on pagan concepts, including the crucifixion of Jesus, point to a motif that supposedly runs across many pre-Christian religions. Basically, there are pre-Christian images/symbols that are similar enough to the outstretched arms of a crucified person, and this idea was taken conscioussly or not, by the earliest Christians when they were inventing Jesus.

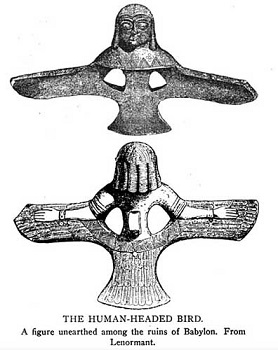

But is such a motif to be found at all in ancient religions tha predate Christianity? Was this motif widespread or even popular at all? Mythicists claim that it was based on idols that were made in antiquity with outstretched arms (called cruciforms), such as these:

|

This represents a person in cruciform (Cyprus, Chalcolithic Period 3900-2500 BC). The cross around the neck represents the throat, as the bottom of the cross is attached to a heart.

|

Isis (winged) on King Tut's sarcophagus |

We can already see that the first and third images are simply the way a person with wings would be depicted, so this is no more a motif than Da Vinci's drawings of a human with machine wings. The second statuette is simply one typical way a human/deity can be sculpted, as this Mesoamerican object shows:

As we can see, outstretched arms are a common enough image for people to come up with independently. There is really nothing that can be said to have proven that Christianity took this ancient (imaginary) motif of the outstretched hands. The hands-by-the-side figure from these same ancient times is just as common as the cruciform, if not moreso:

Other ancient imagery is even more imaginative and unscholarly in terms of proposing a motif for Christianity to copy. For example, I've seen these images cited as evidence, the argument being the outstretched arms!

Is it really to be believed that these examples of ancient iconography influenced Christians to invent Jesus' death as a crucifixion?! Had this really been the case, the mystery religions of Rome, which along with Christianity were receiving a lot of attention and interest in the second century, would have incorporated a crucified/outstretched hands figure. But none of them do until well after Christianity became popular and had brought the crucified motif itself.

Note that none of those depictions are crucifixions, nor depict the death/event as any kind of glorious death/suffering with outstretched arms for this to be a motif in pre-Christian antiquity. Just about the only figure in pre-Christian religious history to have suffered with honor/glory in a position of oustretched arms is Prometheus, whose disobedience in giving gifts to mankind brought about Zeus' anger. But this is no motif, and the only true common factor with Jesus is that a benevolent person/being suffered for the good of others - the suffering/death for a good cause is the only thing that Jesus and Prometheus have in common, not the (nonexistent) oustretched arms motif, as there were many figures in antiquity who were honored as unjustly persecuted sufferers for the good of mankind (e.g. Socrates).

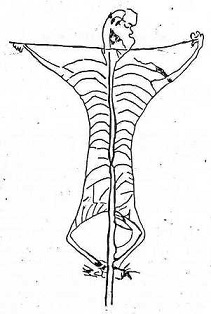

Acharya S thinks that the next two images and related Ancient Near Eastern iconography provided a motif for Jesus and the two thieves crucified on his left and right:

|

Alleged Crucified Thieves Motif Image 1

|

|

|

Yes, she actually thinks that the two hands in the image on the left are a possible parallel to the crucified thieves! Of course, I find the rocks on the right a much better parallel if that's the standard she relies upon.

As for the second image below, it is a Minoan figure with two lions on the side. This is no more a parallel than the Bulgarian coat of arms on its right, which by the way, has a much better claim to being influenced by ancient pagan religions in this case than Christianity:

|

Alleged Crucified Thief Motif Image 2

|

|

|

While it is true that both the Minoan image and the Bulgarian coat of arms were imagined, this simply proves there was no influence, and just because two similarities exist where one was imagined, doesn't mean the other one was.

I will conclude this analysis by saying that we cannot see any ancient, pre-Christian motif of a glorified religious figure whose death/suffering was popularly symbolized by outstretched arms. It simply doesn't exist. I stress "popular", because yes, you'll find someone who happened to have outstretched arms and suffered for a noble cause in pre-Christian religion (Prometheus), but that doesn't mean anything, because for one, his suffering was of a completely different nature (punishment that everyone wants avoided), and two, most importantly of all, this was neither popular, nor common, in pre-Christian religion. To maintain that some figurines/images from ancient times who have stretched arms was an influence on Christians in the first century (who didn't have archaeology to see or be influenced by any of these artifacts), is as plausible as the same pagan religions have influenced these two images:

Occasionally you might see the claim that there were many uses of crucifixion/crucifixes and the cross in pre-Christian religions. Some of the examples are pure fantasy. For example, some point to many ancient statuettes, whose outstretched arms (cruciforms) are misused to say these were used as crucifixes. This is obviously absurd and a cruciform is not a depiction of or anything related to crucifixion. The modern term, cruciform, comes from the similarity of crucifixion, not because they actually represent crucifixions. Proof of this is the fact that any pre-Persian statues/art of cruciform predates crucifixion, which was invented around 500 BC, and popularized on a cross by the Romans, centuries later. So when someone throws an Egyptian hieroglyph of Horus with outstretched arms, this isn't Horus being crucified, but representing the vault of heaven. Osiris' outstretched arms are because he is holding the Sun, and has no relation to crucifixion (which didn't exist at the time).

Even less convincing are the Mesoamerican deities, whose cruciforms are only proof that cruciform is a natural shape into which someone might make a figurine. The cross may have been used in ancient religions (such as the Egyptian ankh and other such hieroglyphs), but this is nothing but a coincidental similarity as is proven once again by similar Mesoamerican shapes. These have no relation to the cross used for the crucifixion of Jesus.

Now, those advocating the theory that Christianity copied pagan ideas usually state that one doesn't need to have pre-Christian crucifixion in religious imagery to have Christianity copy it - one only needs a motif. What I mean is this: the Greek god Ixion was nailed to a wooden wheel which turned in the sky for all eternity. Bacchus' death "in" a tree (literally he became the tree) is also taken as a "motif" of a religious figure's death being associated with something wooden (like the cross). Thus, Christians saw something like Ixion's or Bacchus' deaths and said, hey, that's a popular motif, let's invent our Savior to have been crucified! This is in no way a possibility. First of all, Ixion's nailing to the wheel is a shameful punishment by Zeus, in no way to be equated with the triumph of the cross that was seen as a shameful humiliation by the Greeks and Romans. Bacchus' death is also nothing triumphant. Who would ever copy a motif where the religious figure is embarassed? Not to mention that such a motif (a death associated with something wooden/tree-like) was in no way widespread in the first century (or in any century before Christianity became popular). Ixion and Bacchus are basically the only examples whose deaths resemble (and this word is used very loosely here) crucifixion. This is in no way a motif when there are virtually no examples of it, and the only examples weren't even popular. The Romans and Greeks made fun of the Christians for centuries that Jesus was crucified (1 Corinthians 1:18-25), something the Christians would have known, yet Jesus' death was invented as such! Utter impossibility. Of course, out of hundreds of stories of the deaths of religious figures, a couple of them are gonna be associated with something wooden/tree-like, but we have no motif here that Christians could have borrowed. Cruciforms and crosses, of course, do not fall under this as a motif at all because a cruciform is a pretty simple and common shape a statuette can be made in. A cross is also an easy to come up with shape in religious symbolism. That doesn't mean that it was easy for the Christians to come up with the cross and cruciform because after all crucifixions historically had both, and this is what Jesus' death was connected with. There were plenty of other ways that were popular for Jesus die in, or not die in at all (such as the chariot of Elijah), but Christians choose the most embarassing one - crucifixion? It's simply more plausible that Jesus was crucified than that Christians made up his death. In addition to this, many idols in antiquity are not in cruciform, so it's not like most idols/religious figurines were made in cruciform. Also, the cross wasn't really a big part of any ancient religion.

The last culture that would have used the cross or crucifix as an objection of veneration or religious worship was the Romans (and with them the Greeks). Crucifixion was reserved for the worst criminals. This was one of the points in Christian preaching that made Christianity unappealing to pagans as we see from Paul who writes that:

For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God...Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those whom God has called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than human strength.

First I'll discuss the alleged pre-Christian uses of crucifixion/crosses in art, sculpture, and the like. Then I'll turn to literary sources that talk about this. Thus, bearing this in mind, let's look at actual depictions of crucifixion and see that these works/imageries are either:

A. Non-religious Depiction of Crucifixion - because ancient people painted/carved things out for art/expression/information and not merely for religious use.

B. Depiction of Jesus - so obviously Christianity didn't borrow from this religious group.

C. Influenced by Christianity - clearly not a source for the Christian use of the cross or crucifixion.

Alexamenos Graffito

B. Depiction of Jesus/C. Influenced by Christianity

The Alexamenos Graffito is a Greek inscription on a wall of a building called the domus Gelotiana in Rome. The inscription reads: "Alexamenos sebete Theon", which translates to, "Alexamenos worships God". The inscription cannot predate the year 41, because Caligula acquired the house, and after his death (41 AD), it became used as a paedagogium. Scholars tend to date the inscription to the third century. The Alexamenos Graffito is a Greek inscription on a wall of a building called the domus Gelotiana in Rome. The inscription reads: "Alexamenos sebete Theon", which translates to, "Alexamenos worships God". The inscription cannot predate the year 41, because Caligula acquired the house, and after his death (41 AD), it became used as a paedagogium. Scholars tend to date the inscription to the third century.

How do we know this inscription depicts Jesus as the crucified? The inscription is certainly an insult aimed at Alexamenos worshipping Jesus. The evidence that the crucified person with the head of a donkey is Jesus is the fact that the pagans since at least the second century accused and derided the Christians of worshipping a donkey:

The accusation that Christians practiced onolatry (donkey-worship) seems to have been common at the time. It was based on the misconception of the Jews worshiping a God in form of a donkey. The source of this prejudice is not clear. Tertullian, writing in the late 2nd or early 3rd century, reports that Christians, along with Jews, were accused of worshipping a deity with the head of an ass. He also mentions an apostate Jew who carried around Carthage a caricature of a Christian with ass's ears and hooves, labeled Deus Christianorum Onocoetes ("the God of the Christians begotten of an ass").

Other theories are that this is a depiction of Anubis, Dionysus/Bacchus, Seth, or some gnostic horse-headed figure rather than Jesus. But from the trace on the right, it is clear that the head of the figure is a donkey/horse and not a dog (the muzzle is donkey-like), so this is not Anubis. Nor would it be Dionysus/Bacchus whose only association is the donkey, and the evidence weighs more in favor of either Jesus or a Gnostic worship of Seth. As for Seth (aka Typhon): Other theories are that this is a depiction of Anubis, Dionysus/Bacchus, Seth, or some gnostic horse-headed figure rather than Jesus. But from the trace on the right, it is clear that the head of the figure is a donkey/horse and not a dog (the muzzle is donkey-like), so this is not Anubis. Nor would it be Dionysus/Bacchus whose only association is the donkey, and the evidence weighs more in favor of either Jesus or a Gnostic worship of Seth. As for Seth (aka Typhon):

WŁnsch, however, conjectures that the caricature may have been intended to represent the god of a Gnostic sect which identified Christ with the Egyptian ass-headed god Typhon-Seth (Brťhier, Les origines du crucifix, 15 sqq.). But the reasons advanced in favour of this hypothesis are not convincing.

The identification of the crucified with the Gnostic sect of the Sethinai is certainly a possibility:

From the circumstance that at the right of the ass's head (see p. 222) there stands a Y, WŁnscn deduces that it is a symbol of the Typhon-Seth worship, for on the numerous curse-tablets in Rome the same symbol always stands at the right of the ass's head of Typhon-Seth. It is the religious symbol of the Gnostic sect of the Sethinai (from Seth, son of Adam; but also from Seth, the surname of the Egyptian god Typhon); and they in their turn derived the ass's headóas shown in the above-cited quotation from Epiphaniusófrom the representation of the "Jewish god Sabaoth." WŁnsch is therefore inclined to consider the cult of the ass as having foundation in fact and not merely in calumny.

It is certainly possible that this image depicts a gnostic deity. But even so, should this be a Gnostico-Egyptian/Christian mixture, there is already an influence from Christianity, not the other direction by the fact that the Gnostic heresies took ideas from Christianity. Although Gnosticism was a pre-Christian movement, the Gnostics brought in their heresies in combination with the Church since the early second century, and syncretized Christianity with Gnosticism, not the other way around. Therefore, either way, this is no pagan origin for Jesus' crucifixion.

Orpheus Bakkikos

C. Influenced by Christianity

An engraving of the pagan god Orpheus, an actual crucifixion that doesn't depict Jesus, may be occasionally seen cited by skeptics of a pagan parallel to the crucifixion of Jesus. The problem here is that even if this engraving (which has been lost since World War II) is real, it doesn't predate the years 200-300 AD. So this is hardly a case of Christians borrowing from such imagery, especially since the Orpheos Bakkikos (as it is called) is from the third century AD.

An engraving of the pagan god Orpheus, an actual crucifixion that doesn't depict Jesus, may be occasionally seen cited by skeptics of a pagan parallel to the crucifixion of Jesus. The problem here is that even if this engraving (which has been lost since World War II) is real, it doesn't predate the years 200-300 AD. So this is hardly a case of Christians borrowing from such imagery, especially since the Orpheos Bakkikos (as it is called) is from the third century AD.

Nor is the Orpheos Bakkikos an example of a motif, where Orpheus and other deities were depicted crucified - this engraving is the only such example and antiquity has an entirely different death for Orpheus. If authentic, the amulet (or whatever it is) shows that Orpheus, who was frequently identified with Dionysus/Bacchus (hence Bakkikos) in late antiquity was influenced by Christianity, not the other way around. This is because the death of Orpheus is depicted as the death of Bacchus/Dionysus, who died by becoming a vine, and the identification of this death for Orpheus doesn't predate the year 200, seeing that Pausanias (writing in the late 2nd century) and Ovid writing around the time of Jesus, attribute completely different deaths to Orpheus than that of Bacchus/Dionysus, thus showing that this motif cannot predate the 3rd century or even later.

But what if Dionysus' death was depicted as a crucifixion in the first century (or before), prior to the association of Orpheus with Dionysus in late antiquity? This is also impossible before the influence of Christianity for the simple reason that the whole story/myth of Dionysus would make no sense if the pagans had him depicted as crucified. No story or representation of his death depicts him hung/crucified - his death is simply becoming a vine in some versions of the myth (in others he is dismembered and eaten by Titans, except for his heart), and it's impossible for the myth to have any sense or significance if Dionysus' death was his being crucified. Thus, there is no pre-Christian or contemporaneous with Christianity's origin motif of Dionysus/Bacchus being crucified, and our literary and iconographic sources do not have anything related to a crucifixion either.

Therefore this 3rd century (or later) engraving is best seen as influenced by Christianity, with no earlier elements having influenced Christianity itself.

Pozzuoli Graffito

A. Non-religious Depiction of Crucifixion

The Pozzuoli Graffito is our earliest image of a crucified person. This image of a crucified person is simply a depiction of it. There is no evidence of religious use of this iconography. It depicts a victim crucified on a Tau-cross (not the same as the traditional Christian cross) from behind. At least one scholar has speculated that this was meant to represent Jesus. Another scholar supposes this was the crucifixion of a slave woman because of the long hair and tunic (instead of the animal skin crucifixion victims were usually clad in).

The Pozzuoli Graffito is our earliest image of a crucified person. This image of a crucified person is simply a depiction of it. There is no evidence of religious use of this iconography. It depicts a victim crucified on a Tau-cross (not the same as the traditional Christian cross) from behind. At least one scholar has speculated that this was meant to represent Jesus. Another scholar supposes this was the crucifixion of a slave woman because of the long hair and tunic (instead of the animal skin crucifixion victims were usually clad in).

And so we have another nonexistent case for a non-Christian use of the crucifix.

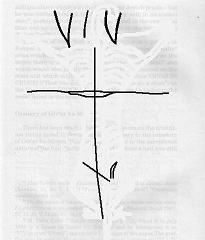

Vivat Crux Graffito

A. Non-religious Depiction of Crucifixion

An iconography of a crucifixion cross (with no victim) comes from Pompeii (79 AD). This imagery simply depicts the cross used to crucify people and does not represent any religious use. Notable features include the fact that it is not a high Tau cross, but the same kind of cross used to crucify Christ. Also, there is a sedile midway to support the weight of the body, with a horn that is occasionally found on such crosses to further torture and mutilate the victims. From Justin Martyr we read:

An iconography of a crucifixion cross (with no victim) comes from Pompeii (79 AD). This imagery simply depicts the cross used to crucify people and does not represent any religious use. Notable features include the fact that it is not a high Tau cross, but the same kind of cross used to crucify Christ. Also, there is a sedile midway to support the weight of the body, with a horn that is occasionally found on such crosses to further torture and mutilate the victims. From Justin Martyr we read:

Now, no one could say or prove that the horns of an unicorn represent any other fact or figure than the type which portrays the cross. For the one beam is placed upright, from which the highest extremity is raised up into a horn, when the other beam is fitted on to it, and the ends appear on both sides as horns joined on to the one horn. And the part which is fixed in the centre, on which are suspended those who are crucified, also stands out like a horn; and it also looks like a horn conjoined and fixed with the other horns.

VII. General Discussion of the Erroneous Methodology of this Parallelomania

One cannot go around citing coincidental, insignificant similarities as evidence of dependence or common origin between two religions. Besides this fact, there are four enormous obstacles to these hypotheses, especially with respect to the origin of Christianity in the first century AD. One, most of the alleged parallels occurred hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of years before Christianity arrived. Many of those examples of alleged dependence (such as the cross representing the sun) stayed in distant antiquity and were largely unknown imagery by the first century. Second, the culture of Egypt was not very influential upon the first century Jews in Judea, and not even in Egypt itself! This can be seen from Philo's writings (who lived c.20 BC - 50 AD), which reflect a syncretism not with Egyptian religious motifs, but with Hellenistic ones, such as Plato's philosophy. How much more would have the Jews in Judea, where Christianity arose, been uninfluenced by Egypt! Therefore, Egypt, India, Africa, Arabia (and especially Mesoamerica!) have little to add to the discussion unless a more relevant example than a hieroglyph in religious use has a cross in it. Third, the very culture of the Jews and earliest Christians (who were Jews) was antagonistic to anything pagan, even to the point where the Jews were considered unclean if they so much as ate with non-Jews. This practice continued very much into the first decades in the Church, as we see in Paul's letter to the Galatians. The numerous riots under Pilate occurred because of the attempt to place pagan images in the Temple. Finally, many of the accounts and motifs that are cited, such as crosses and cruciforms, were neither popular, nor widespread enough for the Jews and Christians to assimilate. These include the minor variations for stories about Horus' birth, and others such as Mithras being the son of a "virgin mother" - which story was in the Persian Mithraism long before, and was long forgotten by the time of the Roman Mithraism which didn't even gain popularity until the second century AD.

With these points in mind, there are numerous parallels and coincidences in history that are much closer to one another than the myriads of vaguely similar religious details of ancient paganism and Christianity seen so far. Some examples of the type of unscholarly logic seen so far are:

- The Similarities between John F. Kennedy and Abraham Lincoln

- The Mythical Napoleon

- Josephus being the same person as the Apostle Paul

- The Similarities between Muhammad and Krishna

And many more. One example I can cite is the old Zoroastrian concept of the Earth having seven regions (Avesta Yasna 32.3; seven being a very special number in Zoroastrianism), and the seven continents in modern geography; clearly Zoroastrianism didn't influence that. With this type of abysmal logic, anything can become anything, and I wish with this type of argumentation and fantasy, that my old 2001 Volvo S40 could become a Ferari.

VIII. Conclusion

So, in assessing the different categories and types of supernatural phenomena recorded throughout history, we should examine how similar each of these are with respect to Christianity and how well they fit in these criteria outlined in the introduction:

- Direct Influence on Christianity

- Indirect Influence on Christianity

- Direct Influence by Christianity

- Indirect Influence by Christianity

- Common Human Imagination

- No Relation

References

- John Ruffle, "The Teaching of Amenemope and its Connection with the Book of Proverbs," Tyndale Bulletin 27 (1976): pp.29-68. The Tyndale Biblical Archaeology Lecture, 1975.

- Carpenter, Humphrey; Tolkien, Christopher, eds. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Letter no. 229. London: George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-826005-3.

- Jan Bremmer. "Scapegoat Rituals in Ancient Greece", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 87 (1983): pp.319-320.

- Plato, Theaetetus 166.a.2

- Plato, The Republic 5.479a

- Is Suetonius's Chresto a Reference to Jesus? (Retrieved July 24, 2013)

- Pliny, Tacitus and Suetonius: No Proof of Jesus (Retrieved July 24, 2013)

- Ibid.

- Suetonius, Divus Claudius 25; cf. Tertullian, Apologeticus 3. I'm aware those such as Acharya S reject the references such as Tacitus and Suetonius, but these unscholarly claims are sufficiently answered.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.44 - Although Tacitus has the correct form, there might be some evidence the original said Chrestus and Chrestiani and was later erased for the correct Christus and Christiani.

- The Chrestos bowl

- Historia Ecclesiastica 4.3.1-2

- 1 Corinthians 1:18, 22-25 (NIV)

- Wikipedia: Alexamenos Graffito

- Ibid.; Tertullian, Ad nationes 1.11, 1.14.

- Hasset, Maurice M. (1913). "The Ass (in Caricature of Christian Beliefs and Practices)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- WŁnsch, "Sethianische Verfluchungstafeln aus Rom," p. 222, Leipsic, 1898

- Jewish Encyclopedia (Retrieved July 25, 2013).

- A. Maiuri, "La Campania al tempo dell'approdo di S. Paolo" in Studi Romani 6 (1961), p.135.

- M. Guarducci, "Iscrizioni greche e latine in una Taberna di Pozzuoli", Acta of the Fifth Epigraphic Congress, IPS: Roma, 1967, pp.219-223.

- Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 91. CCEL. (Retrieved July 25, 2013).

|

|